Introduction

Population policy has always been prominent in the Australian political landscape. The issue defined the make-up of the very first Federal parliament, whilst the ‘populate or perish’ mantra drove post-war immigration from Southern Europe. In 2006, Australia’s then Treasurer Peter Costello encouraged us to have ‘one for mum, one for dad and one for the country’[i]. The recent Federal election saw Australia’s Prime Minister Julia Gillard publicly rejecting a vision for a ‘big Australia’[ii], seen as a call-out to environmentalists and far-right elements, and a counter to the calls for increased migration from business interests and industry groups.

At its heart, this is an argument about population growth – how large should Australia’s population be and what should be the make-up of that population. Although simple in definition, these elements have enormous impact on the future direction of Australian society, and the role it plays in the world. As such, there are many groups who have vested interests in these outcomes, placing it squarely in the realms of political policy.

The purpose of this report is to examine the various elements that contribute to population policy, and propose a framework for population policy in Australia.

Drivers of population

For such a crucial influence on society, population growth[iii] has only three levers:

- birth rate

- death rate

- net immigration rate

Any framework for population policy can only focus on these three levers. In reality, birth rate and death rate can only be indirectly influenced, and this goes some way to explaining the prominence of immigration in the national debate. However, whilst it is attractive to think that immigration policy becomes the primary lever, the reality is that birth rate and death rate are the two main drivers of long-term population trends, and there are limits to the ability of immigration to influence these trends (although in the short-term they can have quite significant impact).

Birth Rate

In the context of population policy, birth rate focuses less on the number of children born in a particular year, and more on Total Fertility Rate (TFR) – the average number of children born to a female over the course of her life, averaged across the entire population. The measurement includes all females, not just those with children, and thus factors in non-reproducing females, a population that has varied historically, and can have significant impacts on population growth. A TFR of 2.0 is referred to as “replacement population rate”, and in crude statistical terms, says that each female will replace herself with another reproducing female. Over time, populations with no net immigration and a negative TFR will decline, although aging of populations can lead to substantial delays before this trend develops.

In a modern secular democracy such as Australia, birth rates cannot be directly impacted by government policy. Incentives and disincentives may be applied to encourage or discourage women (and by extension, couples) to reproduce, but personal preferences, social trends and cultural factors will be far more influential. The declining levels of religious observance in Australia have also diminished the church’s influence in this area, although increasing migration levels from developing countries are seeing the importing of cultural attitudes to reproduction and family size.

Death Rate

Death rate (or mortality rate) is the number of deaths in a population over a 12 month period. It is usually referred to as the number of deaths per 1000 people in a population. A more accurate, but complex, metric is Standardised Death Rate (SDR), described as:

“…the death rate of a population adjusted to a standard age distribution. It is calculated as a weighted average of the age-specific death rates of a given population; the weights are the age distribution of that population.”[iv] This measure reflects the age distribution of the population being described.

“Life expectancy at birth” is another important metric, describing the general longevity of the population. Rising life expectancies have been a feature of recent history, particularly in developed countries, and are primarily the result of medical advances.

The excess of birth rate over death rate in a population is referred to as the “natural growth rate”, and is effectively the population growth rate exclusive of migration. When death rate exceeds birth rate, natural population growth will be negative, and without offsetting immigration, populations will decline. Increases in life expectancy have delayed increases in death rates in many developed countries, but reduced birth rates mean that as populations age, death rates will inevitably increase, and population decline will commence. Depending on the age profile of the population, and the degree of decline in Total Fertility Rate, population decline can gain rapid momentum.

Short of mandatory euthanasia or deliberate government neglect of health services, death rate is something that a government would only seek to reduce, and is therefore a one-way policy direction. It is also a controversial area for government policy to target, and even discussion in the general discourse stirs strong emotions. For this reason, it can be considered a background player in discussion of population, although the aging of society and the health and social transfer implications are issues central to this debate.

Immigration

Immigration is controlled by the federal government. Permanent immigration, which has long-term influence on Australia’s population size and make-up, consists of two components:

- Migration, targeting skilled migrant, family reunions and other migrants covered under the Special Eligibility Stream

- Humanitarian, consisting of refugees and others in humanitarian need.

In 2010–11, the Migration Program [a] had a target of 168 700 places, whilst the Humanitarian Program was allocated 13 750 places. The 2010–11 Migration Program can be further broken down into:

- 54 550 places for family migrants who are sponsored by family members already in Australia

- 113 850 places for skilled migrants who gain entry essentially because of their work or business skills

- 300 places for special eligibility migrants and people who applied under the Resolution of Status category and have lived in Australia for 10 years.

Considerations in the present program include[v]:

- application rates in demand driven categories such as partners, children and employer nominated and business categories

- the take up of state-specific and regional migration categories to achieve a better dispersal of the intake

- the extent of national skill shortages and the ability to attract migrants to these

- the availability of high standard applicants in the skilled categories.

Treaties and agreements between Australian and New Zealand allow for the relatively free movement of people between the two countries. These movements, and specifically permanent and long-term immigration to Australia from New Zealand, are not included in the numbers for Australia’s migration program. This number is difficult for Australian governments to control, and tends to fluctuate based on the relativities of the two economies.

In the 2009–10 financial year 36 519 New Zealand citizens came to Australia as permanent and long-term arrivals[vi].

Population Composition

It is important to remember that the breakdown of that population has a greater influence on society that the raw number. Some elements of population breakdown include:

- Gender balance – fairly inconsequential in Australia, although it is an emerging issue in China, where the confluence of the single child policy and cultural preferences for male offspring, will have created a male surplus of roughly 30 million men by 2020[vii].

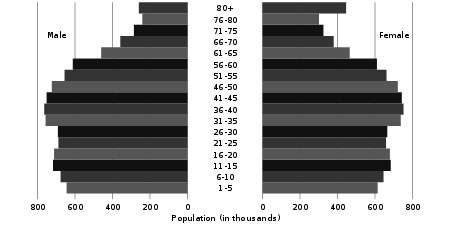

- Age distribution – the aging of the Australian population (a phenomenon faced by most developing nations) has been one of the key forces that have thrust the dry science of demographics onto the front pages of the popular press. At its heart, the extension of life expectancy (almost entirely through medical advances) has created a shifting balance between the available work pool, and the non-working pool with increasing care requirements. One aspect of this situation is the impact on the taxation and welfare systems, with a smaller (relatively) workforce providing the taxes to pay for a growing population of elderly dependents. This aging population has been a key driver of superannuation policy, which in turn has shaped the Australian investment landscape.

Australian Population Pyramid 2005

- Skill distribution – society relies on a broad number of skills to effectively function. Demands for skills (or willingness to participate in certain professions) change over time, and ensuring that the population is able to meet these skill demands is a key challenge for government and industry, particularly in Australia which has relatively free labour and education markets. Skilled immigration (and indeed unskilled immigration) is a key consideration in any population policy.

- Racial/cultural distribution – although controversial, the racial and cultural breakdown of a society can have strong influences. In Australia, the impacts of a multi-cultural immigration policy (beginning in the 70s) have been overwhelmingly positive, with Australia being one of the most integrated societies. None the less, issues of tolerance, cultural and religious conflict, and national character have been routinely raised, and it would be glib to dismiss these as simply the complains of ardent racists. Strong consideration should be given to the impact of large numbers of immigrants from very culturally different countries.

- International relations and obligations – although an island, Australia is still a member of the international community, and highly connected and dependent on other nations. With this interdependence come obligations, like participation in humanitarian programs, such as refugee settlement, and sharing the burden of global problems (such as climate change). Probably the most philosophical consideration in populations policy (invoking such notions as fairness and reciprocity), it is still a factor that must be allowed for.

Current Population Position

As at March 2011, Australia had a population of approximately 22.7 million people[viii], with an annual growth rate of 1.4%[ix]. In the 12 months proceeding March 2011, 46% of growth was natural population growth (births less deaths) and 54% was from net migration.

Australia’s current total fertility rate (the expected number of children born per woman in her child-bearing years) is 1.9 babies per woman. This is below replacement rate, but only slightly, and gives Australia the 60th lowest fertility rate in the world. Several developed Asian countries (Japan, South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong) and European nations (particularly in Germanic, Eastern and Southern Europe) have fertility rates below 1.5 babies per woman[x].

Australian fertility was showing slight signs of decline approaching 2000 (particularly in urban areas), but rose significantly towards the end of the 2000’s, most likely driven by a combination of financial incentives for reproduction, and consumer confidence from a period of sustained economic prosperity. The fertility rate reached a recent peak in 2008 of 1.956, before declining slightly.

In 2009, Australia has a standardised death rate (SDR[xi]) of 6.7 deaths per 1000 people (this compares to a birth rate of 13.7). Death rate comparisons between countries are more difficult, as they are a mix of general living conditions and the age profile of the country. Life expectancy at birth is a better determinant of overall social conditions, and on this metric, Australia has a life expectancy at birth of 81.2 years – the fifth highest figure in the world. These numbers are fairly static, although as the population ages, death rates will increase.

Although trends can be identified in births and deaths, these are relatively slight, and have little short-term impact. Migrations rates, and in Australia particularly immigration rates, can have much more pronounced impacts over a shorter time period. They are also subject to much greater variability, being subject to changes in government policy and economic conditions.

Population Targets

On presenting arguments for population policy direction, advocates will often cite a ‘target’ population to give some tangibility to their case. Of course, without a time scale, these targets are fairly meaningless, and the year 2050 is a population time horizon. In recent years, there has been strong pushes for policies that drive population in both directions, some of which we will cover here. In simple terms, this can be cast as a tug of war between business (big Australia) and environmental interests (small Australia), with far-right elements seeking to focus purely on immigration levels. It is ironic that, as we shall see, the loudest voices are proposing population levels that are unsupportable by any realistic population policy.

Big Australia

The proponents of a ‘big Australia’ have a number of drivers. The aging of the Australian population will present a variety of challenges, particularly economic, and they believe that action needs to be taken to address the coming age imbalance. Simplest amongst these is the notion of increasing immigration, and targeting younger immigrant groups, providing younger workers to support the increasingly aging population and shrinking workforce.

An extension of this case is the more generic perception that a larger population would be more economically beneficial for Australia, with a larger work force, and a larger number of consumers and tax payers driving greater economic activity.

Historically, defense has been cited as a driver for an increased population, but on the back of strong post-war immigration and the mechanisation of modern warfare, these arguments are no longer pertinent to the debate.

Others propose increasing TFRs, reversing natural population decline, through a combination of financial incentives and ‘family friendly’ policies, as well as seeking to shift cultural attitudes towards family size. Whilst some aspects of this group represent well considered arguments grounded in demographics, others are driven by the perception that we are having too many babies of ‘the wrong colour’[xii], and are more driven by racial perspectives than sound policy.

One exception to these broad groups is typified by former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, who believes that Australia does not carry its fair weight in terms of population, given the size and resources of the country[xiii]. This argument is focused on the issue of fairness, and the benefits delivered to immigrants, rather than the well-being of the country itself. This position finds itself at odds with both its fellow ‘big Australia’ advocates, as well as environmentally driven ‘small Australia’ barrackers.

Large scale migration issues to address aging population suffer from the long-term reality that immigrants also get old, and constantly seeking to keep the workforce young requires an ever growing number of immigrants, leading to an exponentially growing population. This raises the challenges of the country’s ability to absorb an increasing number of immigrants, despite fairly well understood upper limits on the maximum annual immigration level. Also, the additional resource demands of immigrants will exacerbate existing resource pressures. Finally, the number of suitable immigrants (skilled, young and ideally with language skills) is finite, and would quickly be exhausted in such a scenario.

Little Australia

Low population advocates, such as Tim Flannery and Harry Recher, believe that Australia’s present population greatly exceeds the ‘carrying capacity’ of the country. Recher [xiv] proscribed proposed zero migration and a single child policy, without setting any particular population target, but applying these demographic variables, would see Australia’s population fall to 5 million by 2098. Flannery suggestion that an optimal population might be 12 million[xv] would require either a significant adjustment to current fertility patterns and/or negative immigration figures of up to 100,000 people per annum.

Both these arguments show the difficulties of achieving rapid population reduction, and limit their discussion of the impacts of what the resulting society would look like. Any reductions in current birth rates and immigration would see an acceleration of the aging issue, accompanied by the economic impacts this implies. Also, once target population has been reached, it would then require a policy about-face to stabilise the population, to prevent terminal decline.

Stable Australia

Given Australia’s TFR is below replacement level, without additional migration, Australia’s population would begin to decline when the death rates rises as the population ages. Several groups are calling for a reduction in immigration levels to keep Australia’s population level stable at its present level, with small amounts of short-term natural population growth, followed by natural population decline.

Although these claims (often featuring in party policy of far-right groups, most notably One Nation at the turn of the century[xvi]) make reference to carrying capacity, resource constraints and environmental issues, the current population level of 22 million people is an arbitrary target, and has neither strong economic nor environmental merits. As the only demographic lever cited is immigration, and in consideration of other platforms proposed by these groups, it is safe to assume that a stable population policy is aimed at preventing immigration, particularly of the non-white kind. Given Australia’s current population mix, it would actually do very little to impact the ethnic diversity within the country.

In the short-term, it would lead to modest population increase through current birth rates exceeding current death rates, but in the future would lead to structural declines.

Demographic realities

Any serious discussion of a population policy should be grounded in realistically achievable outcomes and acknowledgement of the reality and limits of demographics. Specifically, they should be based on what is achievable with demographics, and what the full range of outcomes from such actions are. In a research paper in 1999[xvii], an analysis was made of possible population future scenarios, and quite informatively, several proposed population scenarios were analysed (including some of those identified earlier in this report), along with the ramifications of their pursuit. The key outcome of this research was that none of the proposed population targets could be achieved without significant knock-on effects that would potentially undermine key aspects of social policy. To this end, the report made three recommendations about feasibility criteria for any population scenario:

It should aim to avoid excessive aging of the population

Acknowledging that an aging effect is a demographics certainty, but a population policy should not seek to exacerbate it. Given finite limits to growth, all populations must stabilise.

It should avoid creating a substantial momentum of population decline

As populations naturally age, the death rate may overtake the birth rate, leading to natural population decline (potentially offset by immigration). The issue here is that these are long term trends that can reach a tipping point, and can be difficult to reverse.

It should avoid excessively high or negative numbers of immigrants

Negative immigration would be difficult and undesirable to achieve (leading to either forced deportation or the loss of key human capital), whilst there are a finite number of immigrants that can be attracted and settled in any time period (due to issues such as housing and job availability, as well as general social impacts).

It should avoid wide fluctuations in age structure

Investment in age specific infrastructure (such as schools and nursing homes) is very costly, and it utility can be undermined by rapid changes in the age structure of a society. Converting schools to other purposes is difficult and expensive.

It should avoid a substantial fall in the number of people in the working ages

Reduction in the economic output per capita leads to a reduction in overall societal wealth. Without offsetting technological improvements to productivity, a decline in the number of people working (relative to the non-working population) will lead to falling living standards across the board.

Limits of migration as a solution

Although cited, particularly by large population advocates, as a solution to declining fertility rates, it must be acknowledged that migrants also age, and this will necessitate continued high migration rates to maintain the balance of working and non-working populations. Skills requirements mean that targeting particularly young migrants is not a viable solution.

Population Issues

When talking about population targets, we are talking about the future. Accordingly, projection cannot be mere extrapolations of past trends or present birth, death and migration rates, but rather must take into account the issues that will affect the demographic levers in the future. Although there are a myriad of issues influencing population policy, a number of major future themes are emerging that will have a massive influence on population growth, and must be clearly factored into any population policy.

Aging

A population is considered to be aging when the age distribution begins to skew into older age categories. Australia is already in this position, with the birth rates during the ‘baby boom’ (starting in 1946 at the end of World War 2, and whose end is roughly agreed to be around 1966) exceeding those experienced since. The impact of this affect becomes more noticeable when ‘baby-boomers’ begin to retire, as they will begin to do en-masse in 2011 (assuming a retirement age of 65). Over the next few years, there will be a significant shift in the balance between working and non-working populations in Australia as large numbers of Australians retire, and less Australians join the workforce. This phenomenon is not a surprise, and has been probably the dominant issue in the population policy debates of recent years.

With a mean life expectancy of 81.2 years[xviii], Australia’s older population has several decades before they start to significantly lift death rates, and push Australia into a state of natural population decline. However, this group will take on increased significance for a number of reasons.

Firstly, retirees generally have reduced economic output and lowered consumption to match their (mostly) reduced incomes. Therefore, overall economic activity may decline, and economic output per capita is highly likely to decline unless offsetting improvements are made in workplace productivity. Immigration can assist in this area, but as many retirees have had long working careers, and possess high skill and knowledge levels, there is likely to be productivity impacts with a younger, less skilled workforce drawn increasingly from immigrants. To a lesser extent, the same applies to local younger workers entering the workforce.

Secondly, by dint of the natural aging process, older Australians have higher demands for health care, and an aging population is one in which greater demands are being made on the health system. In Australia, the public health system is the dominant provider of health services, particularly to those who rely on pensions and other government support, such as the elderly. This will increase the proportion of government expenditure that must be devoted to health care. This issue will be exacerbated by the reduced taxation revenue and increased pension expenditure that an aging population causes.

Thirdly, because of the shift from saving to expenditure, retirees, particularly self-funded, but also those drawing on superannuation, will shift the investment and financial landscape, with the liquidation of assets to generate income leading to an excess of supply over demand, and subsequent drops in asset prices. This impact will probably impact later retirees, as the financial actions of those retiring before them will impact the value of their assets, and potentially reduce their wealth leading to retirement. This may require increased government expenditure to fund any shortfalls in predicted wealth levels.

Finally, as a population ages, there is a larger proportion of elderly voters, who will support parties and candidates that address their needs, particularly in areas such as pension support and health care. This increased political influence will have significant impacts on policy and the general political landscape, and could present difficulties in delivering policy that addresses the aging issue at a ‘whole of society’ level. As support for migration tends to decline with age, this could also have impacts on the use of immigration to address the aging issue.

Although these points are generally accepted, there are a few counter-points that should be raised, to ensure the issue has the correct perspective.

Firstly, commentary on reduced economic input focuses purely on the paid labour force, and ignores that contributions made by elderly and retired people to society through volunteer work. This can include both community based volunteering, which reduces the burden on delivering social welfare services on governments, and support of family through activities such as child-care, which frees up parents to allow greater workforce participation.

Secondly, studies have shown that the majority of health care costs related to aging are incurred in the last two years of life, irrespective of the age of the person. Thus, it will not be so much the aging of the population, but the increased death rates when large numbers start exceeding median life expectancy that will drive health costs.

Climate Change

There will be many effects from increasing global temperatures, as predicted by climate change modelling, and Australia is believed to be one of the most exposed countries. This will have several important ramifications in the field of population policy.

Rainfall levels are predicted to drop in a number of key agricultural centres, leading to a likely decline in overall agricultural output in Australia. Whilst Australia exports over 50% of its agricultural output, a rising population match with declining farm production raises the spectre of declining food security, loss of export income due to greater diversion to domestic markets and general economic impact of rising food prices. There are maximum population levels for which Australia could ensure food self-sufficiency (and Australia’s unique geographical position makes it vulnerable to dependencies on imported food), which would need to be factored into any population policy. As the affects of climate change become more apparent, such targets may need to be adjusted up or down, depending on the severity of the impact.

Changing rainfall levels will also impact water availability, and with Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane all experiencing water shortages in the last decade, the need to ensure water supplies, and limit the size of the dependent populations will be a significant factor. Desalination plants will need to leverage clean energy to ensure greenhouse gas emissions are managed.

Environmental damage in more crowded countries (such as rising sea levels and increasingly severe cyclones in Bangladesh) may cause unheard of numbers of environmental refugees, and Australia will have to factor both its international obligations, and the likelihood of a sharp increase in illegal immigration, particularly by sea, into its immigration targets and policies.

Additional impacts will be a potential rise in epidemics, such as mosquito borne diseases like malaria, Ross River fever and Dengue fever, as currently temperate areas become more tropical. These may limit the areas in which populations can expand, and may drive further southerly migration into the already crowded eastern coast between Sydney and Melbourne.

Peak Oil

Rising oil prices triggered by dwindling supplies and increased global demand will have severe economic impacts worldwide. Australia is particularly susceptible to this phenomenon, due to low oil reserves and a highly distributed population, with a small number of significant population centres, separated by long distances. Likewise, much of Australia’s agricultural produce is removed from the population centres it feeds, and the world markets it is sold on.

Low domestic and off-shore oil reserves will see a larger part of our national expenditure spent on oil, crowding out expenditure in other areas. As oil consumption is correlated with population size, this may act as a limit on population growth. Rising prices will also reduce standard of living and tax receipts, which impact the ability of governments to deliver social services, particularly to an aging population with reduced economic output.

Oil prices will translate into petrol prices, and the evolution of Australia’s major cities sees large portions of the population dependent on motor vehicles. Unless massive expenditures in public transport are made (which would compete with other avenues of government spending), people in the outer suburbs of Australia’s key cities would face significant financial pressures from increased petrol prices. It would also limit the ability of governments to grow these cities geographically to accommodate growing populations. Likewise, some regional centres would become less desirable due to their large travelling and transport costs. Higher population densities closer to city centres or a move to more decentralised cities could address some of these issues (with associated drawbacks of their own), but rising energy costs are likely to act as a barrier to population growth in the future.

Policy Framework Contributors

There are a number of factors that need to be considered:

Economic Factors

Central to any debate about population policy are the economic impacts of various population scenarios. Economic factors present perhaps the broadest range of variables and the greatest amount of internal tension between these various dimensions. Core to economics is the impact on the labour market. Excessive population beyond economic capacity may lead to unemployment and underemployment, and create increased demands on public funds through the welfare system, and other social issues related to unemployment. Conversely, a labour force below that demanded by the economy can lead to resources and capital underutilisation, and potential inflation issues. Labour excesses and shortages need to consider not only the size of the labour pool, but also the skill profile of the labour pool. Skill mix, skill shortages, and the proportions of skilled and unskilled labour take on increased significance in a modern economy such as Australia where service/tertiary industries are the dominant employers, and high degrees of technology usage dominate most industries.

Population policies also influence the size and composition of the domestic market, which is a key contributor to levels of economic activity. A large population may allow a critical mass to be achieved in a domestic market, triggering industry growth and economic benefits. A comparison between domestic industries in Australia and New Zealand can provide useful insights into the critical population sizes required to sustain particular industries (as can a comparison between Australia and a large European country such as Germany). Many supporters of a large Australian population cite an increased number of consumers and their positive impact on economic activity as a justification for their targets. Industries such as housing and consumer goods manufacturers are particularly vocal in this area.

With nearly all economies dependent on the taxation of economic activity to support government services, the proportion of working to non-working members of the population significantly influences the ability to provide social welfare. In an ageing population, the proportion of non-workers being supported by workers rises, and may place a disproportionate burden on workers. In 1999, there were five Australians working for every person of retirement age. This ratio is predicted to fall to 3½ in 2021 and 2½ in 2051[xix]. However, such calculations make assumptions about the dependency of retired populations on government pensions and welfare, and Australia’s broad superannuation policies may go some way to offsetting these dependency levels.

Declining workforce levels (either absolute, or relative to non-workforce participation) can potentially reduce economic output per capita, requiring increases in productivity to offset this decline, or leading to a reduction in economic activity within the economy.

Economic activity, and shifts in population age can influence other economic factors, such as assets prices. Housing demand and prices, share prices and other financial instruments can all be impacted by these shifts. As aging populations seek to finance their retirement, they tend to liquidate assets, increasing supply, and driving prices down. As these prices are critical to the income levels these assets can generate, there develops a conflict in these markets. Similarly, as savings are reduced through expenditure, capital for investment in infrastructure (which would ideally boost productivity and offset declining economic output per capita) diminishes.

These are all examples of economic factors that must be considered in a population policy framework.

Environmental Factors

Central to any discussion of population policy is the notion of resource constraints – the availability of key resources essential for survival and economic sustainability. Globalisation and trade reduce the need for a particular location to provide all the necessary resources, and indeed allow a far larger global population than would otherwise be supportable on resources sourced locally. After agriculture, trade was one of the key enablers of civilisation.

None-the-less, there are some resources that are not easily or economically imported, such as water. Further, imported goods must be paid for with exports, and so a region must generate enough value in locally produced goods and services to pay for it requirements, meaning the resource constraint problem can never be truly avoided.

Many of the voices in the Australian population debate believe that Australia’s population exceeds what the country can properly support, and that a reduced population is needed to match our capacity. This argument believes that the price of over consumption is the long-term degradation of the environment and resources, which will eventually collapse and bring their own population pressures.

The famous work of Thomas Malthus, “An Essay on the Population Problem”, contrasted the exponential growth of populations with the linear growth of food supply, and predicted that the growing gap would be narrowed through a combination of catastrophe and misery. Although controversial, this basic premise – exponential versus linear growth – holds true, and although technological advances have done a magnificent job of increasing the gradient of the resource curves, resources remain finite.

Any population policy needs to consider the resources essential for Australia’s well-being, and what the implications for these resources are at particular population levels. Some key considerations are:

Food production

Although Australia exports a large proportion of its agricultural production, food security is one of the basic requirements of any society. Greater population levels will mean greater food requirements, and greater demands on our agricultural inputs and outputs. Further, feeding a larger local population will necessitate diverting food destined for export, impacting the national income levels. As world food prices rise, there will also be an opportunity cost in diverting resources from export to domestic consumption.

The historical answer to growing agricultural demand has been to grow more food, and historically the limitations on output levels have been limited more by demand than resource constraints. However, several key issues pose potential limits to total agricultural output, and accordingly, the size of the population that can be supported.

Water

River health and irrigation usage are high profile national issues, with the Murray Darling basin the subject of heated political and legal battles, and much of Australia’s agricultural output is dependent on irrigation. With a finite amount of flow, and the needs of existing river ecosystems, water stands as the largest factor that will determine Australia’s agricultural output, and thus its supportable population.

Climate change, and predicted changes in rainfall patterns need to be considered, so that a population policy will be consistent with future water volumes.

Beyond agriculture, water is also heavily used for domestic and industrial consumption (mining is a particularly large water user), and both of these uses is also driven by population levels. As well as water quantity, the quality of our water systems, particularly for human consumption, is also important. Many of the pollutants that affect the water cycle are proportional to population levels.

Arable land

Although Australia has massive amounts of land, most of it is entirely unsuited to agriculture. Indeed, much of the land that is farmed is deemed marginal for agriculture, with resultant impacts on yields and reliability. Further, issues such as salinity and top soil erosion are reducing the quantity of arable land, meaning little land is available for expansion of agriculture. Added to this, most of Australia’s most fertile land is located in coastal regions, where the vast majority of the population live, and where population growth is greatest. This means that land that is both suited to agriculture and is close to the markets for its output is being converted to residential and commercial/industrial purposes, further reducing agricultural output.

Climate change is likely to be a key future influence on arable land, and all modelling indicates a decline in rainfall in key agricultural regions, leading to likely further declines in the volume of arable land.

Carbon emissions

Although progress seems glacial at times, international consensus for the need to reduce carbon emissions is growing, and nations will have limits or costs associated with carbon dioxide output. These limits will be most likely per capita, and therefore population levels will drive the costs associated with carbon reduction. Although a decoupling of carbon and population may be achieved in the future, the transition to a low carbon economy will take considerable time and resources, and population levels will be a key influence on the pace, price and success of this transition.

Social Factors

In between the tug-of-war between the economic accelerator and the environmental brake lies the day to day business of living. Although these two factors are key presences in our lives, social factors loom largest in our everyday experience, and are key considerations in a population policy.

Some key social factors that should be considered in a population policy include:

Population distribution

Despite its vast open spaces, Australia is one of the most urbanised countries in the world. Over 70% of Australia’s population live in its 10 largest cities[xx]. When determining population policy, the sustainability and suitability of present and forecast population distribution needs to be factored in. Can desired population distributions (such as a push to create and strengthen regional centres) be achieved, and what policy is required to support this?

Infrastructure support

Changes in population levels will change demand on various elements of infrastructure. Schools, hospitals, aged-care facilities, roads and public transport are just some of the considerations in determining appropriate population levels, and also drive public and private investment.

Housing

This is a special consideration, particularly in the area of immigration, ensuring that appropriate amounts of housing are available, to allow new migrants to be settled without excessive impact on property markets. As migrants may not have large amounts of equity, particularly those from less developed countries than Australia, ensuring affordable housing availability is also a key factor.

Employment

Although a macroeconomic element, the availability of appropriate employment opportunities, and the likely impact on the existing job market and wage levels needs to be considered. Unemployment or lack of job prospects within migrant populations can impact the effectiveness of migration programs; particularly those based on economic factors, and exacerbate known and existing social problems caused by unemployment.

Age distribution

As discussed in the section on aging, different age structure present different challenges to a country, and a population policy should seek to promote a sustainable age structure that is consistent with infrastructure.

Cultural Factors

A culture is a shared set of beliefs and/or behaviours within a group. Although Australia is a land of significant diversity, a number of broad themes run through our psyche. Whilst this culture is subject to constant evolution, it none-the-less forms a key part of the identity of people and groups within it, and the impact of a population policy on culture cannot be overlooked in the framework mix. The most visible and contentious aspect of population policy on culture is that of immigration, particularly from racially and culturally different countries. The White Australia Policy drew its sustenance from the belief that different races would not be able to assimilate and integrate into Australian society (as well as straight out racism), and would undermine social cohesion (never mind the sectarian clashes between English and Irish immigrants). Until restrictions were lifted in the mid-70s, this attitude prevailed.

High levels of immigration, particularly when concentrated from particular areas (Southern Europe in the 50’s, Vietnam and Lebanon in the 70’s, Asia in the 80’s and 90’s, and most recently Africa) can create anxiety between racial/cultural groups, particularly if the immigrant groups are geographical concentrated (as they tend to do out of comfort and preference, as well as some government settlement policies).

Whilst some may claim that these issues are exist only in the minds of narrow-minded bigots, the reality remains that high levels of immigration can create social tension, particularly in less-affluent areas where a) new immigrants, particularly humanitarian migrants, tend to congregate and b) social disadvantage has bred greater xenophobia. Accordingly, the cultural mix, and its likely geographic dispersion, must be considered. The racial/cultural breakdown, although fraught with high emotion, is a serious policy consideration.

The other cultural impact of population policy is in the area of birth rate trends. Long term trends to either increase or decrease the underlying natural population growth rate will involve influencing reproductive beliefs. Cultural and personal issues, such as a shift to smaller family size, would need to be addressed, particularly when larger family sizes involve greater expenditure (a key problem in Japan). Likewise, cultural sub-groups with traditions of large family sizes are likely to baulk at any government attempts to encourage smaller family, and welfare groups would protest reduced financial support for large families.

Finally, the question of whether migrants adopt the reproductive patterns of their destination country needs to be considered, as the answer would influence the longer term affect of immigration on the overall demographic future.

Population Policy Comparisons

When assessing Australia’s population policy direction, it is worthwhile to examine the initiatives taken by other countries in this area. To this end, we have chosen to examine the population challenges and policy responses of three countries.

For the purposes of examining a country with strong similarities to Australia, we have chosen Canada.

To investigate the policy responses of a country facing a declining population (as Australia might were it to drastically reduce its immigration intake), we have chose Japan.

Finally, to examine the challenges faced by a country with a rapidly growing population (which might exist, albeit with different characteristics, in a high immigration model in Australia), we have chose Nigeria.

Canadian Population Policy

Australian and Canada are often grouped together as highly similar countries. They are large countries, but with low population densities. They have comparably sized populations (Canada is about 50% larger) and economies (Canada is about 25% larger). Their economies are primarily driven by resources and agriculture. They are both influential second tier nations, with stable, but active democracies.

They share a similar colonisation background, with a predominantly British influence. They are both predominantly English speaking (Quebec not withstanding), and have large migrant populations, with fairly successful multicultural assimilation (both countries have over 20% of the population born overseas, and immigration makes up over 50% of annual population growth)[xxi]. Demographically, they are also closely matched in Total Fertility Rate (1.79 to 1.53), death rate (7.1 to 7.4 deaths per 1000 population) and life expectancy(81.2 to 80.7)[xxii].

The most striking difference is the long land border Canada shares with the USA, which contrasts with Australia’s purely maritime boundary. Although a potential source of illegal immigration, its influence more strongly tends to foreign workers moving from Canada to the USA

A couple of key differentiators between the two nations, with regards to population influences:

- Canadian immigration is managed at federal and provincial level, making for a more bureaucratic process

- Australian selection criteria, particularly for skilled migrants, are tighter than Canada’s. These differences include assessment of qualifications, access to social security (2 year waiting period in Australia for non-humanitarian migrants), official language proficiency and age (Australia has an upper age limit on skilled migrants of 44)[xxiii]

- Canada has historically had a higher labour participation rate and a higher proportion of skilled migrants[xxiv]

Canada, and to a lesser degree Australia, face the issue of ‘brain drain’, whereby valuable knowledge workers emigrate to other countries (predominantly the United States for Canada, whilst Australian emigrants settle in a broader range of destination countries). Government policies have been implemented, focusing on building a knowledge economy through “tailoring the immigration system to build human capital, spending millions of public dollars on research and development, and reinvesting in universities.”

Like Australia, population policy is an emerging issue in Canada, but the government has no formal policy on population targets. The Liberal Party of Canada has a policy of targeting an immigration rate of 1% of population[xxv], driven by commercial and industrial interests. Despite policies on snow mobile trails and defibrillators at ice hockey rinks, Canada’s governing Conservative Party has no official policies on population or immigration targets[xxvi]. The opposition, leftist New Democratic Party has a raft of policies on issues pertaining to population, such as environmental protection and humans rights, but no specific policy on population targets.

Japanese Population Policy

The Japanese Government considers that the tendency of the young to delay marriage, related to difficulties of balancing work and child rearing, is the direct cause of the country’s declining fertility rate. Therefore, the Government considers it necessary to make concerted efforts both to alleviate problems arising from the strains of balancing work and child care and to enhance society’s support for raising children[xxvii].

In the area of population demographics, Japan stands in stark contrast to Australia’s almost Goldilocks-like balance of slight population growth. Japan faces one of the lowest birth rates in the world, coupled with highly restricted immigration policies. Although no measurable inter-census population decline has been measured, Japan’s population imbalance is well-understood, and without a socially difficult program of mass-migration, will soon begin a possibly irreversible decline.

Japanese Total Fertility Rates (TFR) have steadily fallen since the 1970s, and coupled with a much shorter baby boom in Japan (compared to most other developed countries), Japan’s population is rapidly ageing. When the baby boom demographic begins to enter the age period beyond mean life expectancy (a world leading 82.1 years[xxviii]), death rates will greatly exceed birth rates, and population decline will commence.

The causes of Japan’s low fertility rate are highly cultural, but tied to the broader themes of increased gender equality and advances in female education that underpin declining fertility rates in many countries. Although confronting the future challenges of population decline has received significant attention in Japan, present issues around supporting an ageing population (particularly in a country where this role is traditionally borne by an increasingly dwindling offspring), are possibly more dominant policy issues.

These issues include:

- financing social welfare and pension payments, to a growing dependent population from a shrinking workforce. “In 1997 there were 4.4 workers for every one retiree, by 2020 it is predicted that this ratio will have been reduced to two workers for every one retiree and by 2050 the figure will be 1.5 for every retiree.” [c]

- the potential for resource ‘misallocation’ between generations as an increasingly ageing population carries more political force (sometimes termed a ‘gerontocracy’)

As Japan seeks to encourage higher birth rates, one of the key barriers to such increases is the economic pressures felt by younger Japanese. An increased taxation burden to fund inter-generational payments will increase this pressure, and is likely to further drive down TFR. Further, to increase workforce size, Japan has sought to increase female participation rates, but this again is a downward driver of TFR.

Japan has introduced as broad number of policies in an effort to address is population issues, including[xxix]:

Aged care:

- Pension reform: increases to the pension eligibility age, raising contributions, reducing benefits

- Push for self-funding of retirement income

- “New Gold Plans” – initiatives, beginning in 1990, to address issues around aged care and its funding

Child allowances

- Increasing allowances paid to families, with payment increasing for multiple children, encouraging larger families

- Increasing age of children for whom benefits are paid

- Providing strong support for child-care leave, through the various “Angel” plans

- Increasing funding for child care facilities

Gender equality

Significant legislation has been enacted to encourage gender equality in Japanese society. This is an attempt to counter strong gender asymmetries in Japanese societies, with the belief that sharing of child rearing duties will increase fertility rates. However, existing cultural norms, such as the view that women must leave work to raise infant children, are strongly countering these attempts.

Japan’s historical and cultural resistance to migration removes the third leg of the chair, and frames Japan’s population policy as one of pure birth rate/death rate demographics. Much like discussion of death rates, this is a controversial topic in Japanese society and politics, making considered discussion difficult.

Nigerian Population Policy

To achieve sustainable development and a higher quality of life for all people, Nigeria shall promote appropriate policies including population-related policies, to meet the needs of current generations, without compromising the ability of future generation to meet their own needs.

National Population Policy, 2004

As the most populous country in Africa, and the seventh most populous in the world, Nigeria faces the challenges of both as large and rapidly growing population, and the challenges shared by all sub-Saharan nations, particularly in moving from a developing to a developed nation. Nigeria has a key advantage in this journey over most other African nations, and that is its oil resources, providing valuable export income that can be used to finance its development ambitions.

Nigeria’s current population is estimated at 155 million, with an estimated TFR of 4.73 (offset slightly be an infant mortality rate of nearly 1%), and an annual growth rate (natural increase) of about 3.0 per cent. Although this is declining from a high of 3.3 % in 1990, the demographic engine is set to deliver continued population growth for the foreseeable future[xxx].

A relatively low mortality rate of 18 per 1000 (compared to its African peers), a declining infant mortality rate, and a rising life expectancy all add to the population pressures faced.

Unlike Australia, Japan and Canada, Nigeria adopted its first formal population policy in 1988, which stated:

…reflecting new approval on the part of policymakers of national efforts to curb population growth. Specifically, the policy seeks to reduce fertility from the present level of 6 children/family to an average of 4 children/family, suggests an optimum marriage age of 18 years for women and 24 years for men, and advocates that pregnancies be restricted to the 18-35-year range and at intervals of 2 years.

A second population policy was adopted in 2006, which contained the following goals and targets[xxxi]:

The Specific Goals

· To achieve sustained economic growth, poverty eradication, protection of the environment and provision of quality of social services.

· To achieve a balance between population growth rate and available resources.

· To improve the productive health of all Nigerians at every stage of the life cycle.

· To accelerate the response to HIV/AIDS epidemics and other related health issues.

· To achieve a balanced and integrated urban and rural development.

Target

1. Achieve a reduction of the national population growth rate to 2 per cent or lower by the year 2015

2. Achieve a reduction in total fertility rate of at least 0.6 children every five years.

3. Increase the modern contraceptive prevalence rate by at least 2 percentage point per year.

4. Reduce the infant mortality rate to 35 per 1000 live births by 2015.

5. Reduce the child mortality rate to 45 per 1000 live births by 2015

6. Reduce maternal mortality ratio to 125 per 100, 000 live births by 2010 and to 75 by 2015.

7. Achieve sustainable basic education as soon as possible prior to the year 2015.

8. Eliminate the gap between men and women in enrollment in secondary school, tertiary, vocational and technical education training by 2015

9. Eliminate illiteracy by 2020.

10. Achieve a 25 per cent reduction in HIV/AIDS adult prevalence every five years.

Because of the progress still required in the areas of infant, child and maternal mortality, and the impact of these factors on population growth, increased emphasis on reducing birth rates, through greater spacing of child birth, reduced family size and increased use of effective contraception, is a key population policy priority.

Conclusion

When determining a population policy, there are a number of competing elements to be considered, and like all policy, the associated costs and benefits needs to be balanced. The key challenge in this area is the long-term nature of the underlying drivers, particularly birth rate, and the limited ability for governments to control population in a granular manner.

Whilst immigration is cited as either a savior or a demon in this field, the reality is there are narrow bands in which immigration policy can operate, and the aging of the migrant population limits its utility as an offsetting agent for the challenges of an aging population. Likewise, zero or negative immigration is not a realistic policy option, with only a subset of migration (primarily skilled migrants) being easily adjusted.

Emerging issues such as climate change and rising energy costs will need to be considered, as well as existing challenges we face.

A key requirement of population policy is to be grounded in realistic and achievable objectives. The most vocal proponents for both large and small populations refer to population targets that are either unreachable, or would have such massive impacts as to be unrealistic. Aging of the population is as issue, and a population policy should not seek to exacerbate it, but at the same time, it should acknowledge that the problem cannot be solved by blunt instruments such as immigration, and rather requires technical and social solutions.

Looking at the steps taken by other countries to address their population issues will provide a useful perspective. Countries that are currently facing issues that loom on Australia’s horizon may alert us the success or otherwise of policy measures, and some of the factors we need to consider in our planning.

Finally, population policy must be kept in perspective, particularly the small degree of control we have over population, and the long lead times for changes to impact. Relying on population policy alone is not an option.

[iii] which, if negative becomes population decline, but we will use the term ‘population growth’ to describe changes in population, either positive of negative.

[iv] http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Glossary:Standardised_death_rate_(SDR)

[v] All figures sourced from http://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/20planning.htm

[viii] ABS Population Clock http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3101.0

[ix] All figures sources from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Australia

[xi] “The standardised death rate, abbreviated as SDR, is the death rate of a population adjusted to a standard age distribution. It is calculated as a weighted average of the age-specific death rates of a given population; the weights are the age distribution of that population.” http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Glossary:Standardised_death_rate_(SDR)

[xii] http://www.theage.com.au/news/National/Liberal-MPs-gaffe-on-abortion-pill/2006/02/13/1139679501948.html

[xiii] Weekend Australian, May 3-4 1997

[xiv] Lecture given at Edith Cowan University, 11 July 1997

[xv] Flannery, T, “The Future Eaters”, Grove Press, 2002

[xvi] Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, “Immigration, Population and Social Cohesion Policy”, 2 July 1998

[xvii] “McDonald, P, Kippen, R, “Population Futures for Australia: the Policy Alternative”, Parliamentary Library, 12 October 1999

[xix] “The Right Mix: Toward a Population Policy for Australia”, speech to the Business Council of Australia by Shadow Minister for Population, Martin Ferguson, on 15 November 1999

[xxii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_sovereign_states_and_dependent_territories_by_fertility_rate

[xxiii] “A Comparison of Australian and Canadian Immigration Policies and Labour Market Outcomes” - http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/pdf/comparison_immigration_policies.pdf

[xxv] “A Strategy for A National and International Population Policy for Canada” http://populationinstituteofcanada.ca/keypapers.php?s=keystrategy

[xxvii] Population Bulletin of the United Nations 2002: “Policy Responses to Population Decline and Ageing”

[xxix] Ko, Kyeung, and Ogawa, “Aging Population in East Asia: Impacts on Social Protection and Social Policy

Reforms in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan.”p.56.

[xxx] All figures sourced from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Nigeria

[xxxi] Mazzocco K., “Nigeria’s new population policy.” Int Health News. 1988 Mar;9(3):1, 12.

http://www.population.gov.ng/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=116&Itemid=101